Eric Mondres, 26, a Department of Agriculture staffer, is less cheerful about his addiction. "It's like a drug," he says. You see the same people here week after week. I've tried to wean myself. I'd like to have back all the money I've spent." Near by, wearing a wet raincoat and steamy glasses, a middle-aged man jabs furiously at the thruster of a Star Castle game. He admits to being an attorney in private practice, but says, "I'd really rather you not use my name. This is my secret place. It would drive my wife crazy. I really don't come here very often." Two hours later, he is still there battling the machines alien psychology—and his own.

An onlooker watching such a scene and disposed to gloom would have no trouble detecting the smell of society's burning insulation. Contrariwise, an optimist sees these lunchless loners as sensible adults wisely granting themselves a period of therapeutic play, avoiding the intake of cholesterol and booze, and emptying their minds of clutter by a method quite as effective as meditation. In Japan, where many of the games originate, a 29-year-old magazine executive named Shozo Kimura, who admits the games have hooked him, views the mass addiction moodily: "Tokyo is a big town. You think you are not lonely, but it is the opposite. People have nothing to do. They don't care about anything. They can't buy houses. They can do nothing with their money except play the games."

The video-game craze, more frenzied even than the universal lust for designer jeans and Kalashnikov assault rifles, has spread across the globe. In West Germany, merchandisers are toting up astonishing Christmas season sales figures that may reach $88 million for home-video consoles and cartridges. In Australia, the quarter-eaters, actually 20¢-piece eaters, bring in $182 million a year. Fascination with the games, often accompanied by cosmic brooding about their presumed bad effect on faith, morals and school attendance, seems to be universal. The games have appeared in Arab settlements in Israel, and in Soweto, Johannesburg's huge black township. Brazil's laws forbid the importing of video games, so they are manufactured locally, and are given the necessary touch of international chic with such English names as Aster Action and Munch Man. In Mexico City, the hot arcade is Chispas ("Sparks"). Video arcades are replacing pool halls as the traditional lounging places for young men in Madrid.

Homosexual cruising is a problem in Amsterdam's arcades. In Stockholm, the games are associated in the public mind with

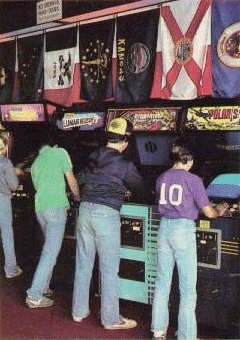

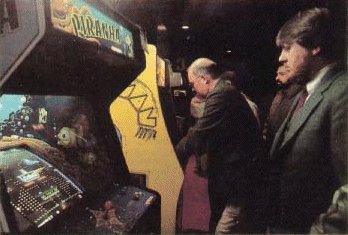

Coat-and-tie types in

Washington work out on machines at L'Enfant Plaza arcade

| teen-age hoodlumism

involving drugs, prostitution and illegal hard

liquor. Video addicts under 18 are banned from

arcades in West Germany, although younger

teen-agers manage to play on home sets in

department stores. In the Philippines, outcries against "the ravages of a destructive social enemy, the electrical bandit," as one infuriated citizens' group called the video games, reached such a level of indignation that President Ferdinand Marcos banned the machines in November and gave owners two weeks to smash them. The Catholic Kids

at Palatine, Ill., mall blast away while parents

shop |

Women's League of Caloocan

City applauded the ban, asserting darkly that the

games had lured young men into beer houses, where

they saw burlesque dancers. A wealthy businessman

was reduced to public despair because the games

had caused the ruin of one of his children, a

17-year-old son whose infatuation with gadgets

was so complete, he refused to attend school or

even see his friends. The distracted father

thinks of sending the boy to school in the U.S.,

but has doubts about it, because "I fear the

video games will, catch up with him there."

He says that "when it finally dawned on me

what had hit me, my first impulse was to put up a

video-machine parlor and let my son manage what

he enjoys doing most. But then my wife prevailed

on me, begging me not to, saying that if I went

ahead with my plan, how many more young boys and

girls would be ruined?" In the meantime the

arcade owners, who, of course, merely hid their

machines, are lobbying President Marcos to relax

his ban. Not long ago, 50 disassembled video

games, listed as "rectifying apparatus

parts," were seized by Philippines customs

agents. In Hollywood, on the other hand, Producer Frank Marshall thinks the video games are "great if you want to take 15 minutes and block everything out. When you're shooting a movie, you're constantly on this high level of adrenaline, and these games use that level to completely absorb you." He kept an Asteroids machine in his office during preproduction work on Raiders of the Lost Ark. "It got out of hand," he confesses. "People actually got fired for spending too much time |