| to speak, to give video

games no quarter. The town fathers of lrvington,

N.Y. (pop. 6,000), rose up in wrath last July and

passed an ordinance designed "to protect the

adolescents of the village against the evils

associated with gambling" (though video

games offer no cash payoff and indeed almost

never click out a single free game); they limited

each establishment to three machines. Ralph

Provenzano, owner of a deli opposite the

lrvington Middle School, resents the suggestion

that he is corrupting the youth, but agreed to

turn off his three machines (Defender, Pac Man

and Centipede), before the start of classes each

morning. With some justice, he says, "I

baby-sat a bunch of kids here all summer. It may

have cost them money, but they were here, they

were safe, and they didn't get into

trouble." The fears that occasionally are voiced of drug-buzzed, beery teen-agers hanging around video parlors in menacing packs seem absurdly exaggerated, and the likelihood is that communities with troublemaking youngsters had them before the arcades opened. But the video games are enormously addictive, and they do eat a lot of quarters. Atari, one of the leading video game manufacturers, advertises a cheerful, fast-moving and very popular arcade game called Centipede with the words "Chomp. Chomp. Chomp. Chomp. Chomp" above a drawing of a voracious looking centipede gnawing a coin. An adult observer in New London, N.H. (pop. 3,000), wanders into Egan's, a pizza parlor with twelve video games, which has become the town's teen hangout since it opened a few months ago. The |

place is clean and friendly, with no smell of funny cigarettes (many arcades sternly forbid smoking of any kind) and nothing in sight more menacing than an anchovy pizza. But a conversation with a twelve-year-old boy who is holding his own against Scramble, a Stern Electronics game in which the player tries to fly a jet through what looks like Mammoth Cave, produces unsettling information. "I usually bring $20," says the boy, when asked how much money he spends. As the observer is digesting this, the boy adds, "But today I brought $40." Proprietor Bob |

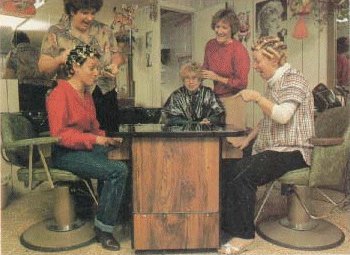

Linda Starkweather works on hair

while customers have fun with tabletop video game

In Orlando, Fla., the consensus of fifth-graders at Blankner Elementary School is that $3 is a "minimum satisfactory amount" to take to an arcade, but several children talked of spending $20. "I used to spend money on my bike," one boy said ruefully. Not all game players throw huge sums into the coin chutes, bin they agree that it takes an investment of between $20 and $50 to become proficient at any game challenging enough to be fun. There is no question that the money drain is one reason why such communities as Babylon, Long Island. Oakland, Calif., Pembroke Pines, Fla. and Durham, N.H., have passed ordinances restricting play by teen-agers of various ages. The New Hampshire Civil Liberties Union asked that enforcement be postponed till the U.S. Supreme Court rules on an ordinance passed in Mesquite, Texas, forbidding play by people under 17.

Lower courts have twice struck down the ordinance.

The fact is, however, that teen-agers hoping to bankrupt themselves blissfully with a session of Asteroids or Missile Command may be frustrated not by a prejudicial ordinance but by a lunchtime crowd of adults monopolizing the machines. The Station Break Family Amusement Center in Washington's L'Enfant Plaza opens at 7 a.m.; by 7:15 a dozen men in business suits are blasting away at the games while coffee in plastic cups grows cold. L'Enfant Plaza is within walking distance of at least five major Government agencies. "Office workers seem to need to blow it out" in their fantasies more than other people, says Tom McAuliffe, 33, vice president for operations of the 51-store chain that owns the arcade.

By lunchtime, with no teen-agers and not one pair of blue jeans in sight, the 47 machines are making a commotion like Mount St. Helens clearing its throat. Curt Myron, 37, is there, a mortgage supervisor at HUD, who is one of the arcade's top guns. Years ago, pinball cowboys would tape notes to the sides of the machines boasting of their best scores. One of the cleverest come-ons of the video games is circuitry that congratulates hot-shooters with GREAT GAME! and the opportunity to record on-screen their initials and scores for a display that flashes periodically. It is the solid-state equivalent of "D. Boone Killed a Bar," and it means that Myron, who earned the four top scores on the arcade's Centipede machine, is held in awe by the other regulars. He skips lunch, he says, and plays every day, so proficiently that he rarely spends more than 75¢. "I also play in airports,"